Corrosion and Its Challenges for the Mechanical World

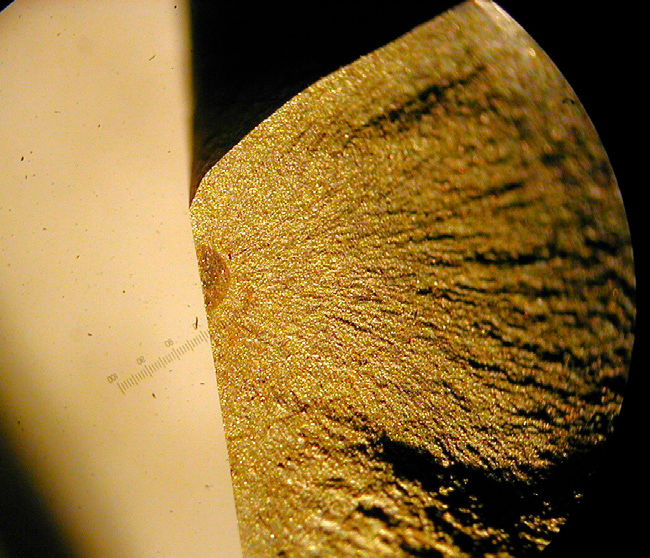

Sometimes corrosion is attractive. For example, the vivid colors on titanium jewelry are oxides, with the color difference the result of the oxide thickness and the refracted light. Also, from an artistically oriented viewpoint, the golden-brown appearance of many of the new high-voltage towers made from ASTM A 242 (Corten) steel is more appealing than their bright galvanized cousins, and that “pleasing brown color” is a tightly bonded coating of rust. But most of the time, and in several ways, corrosion presents difficulties that can greatly shorten the life of mechanical equipment.

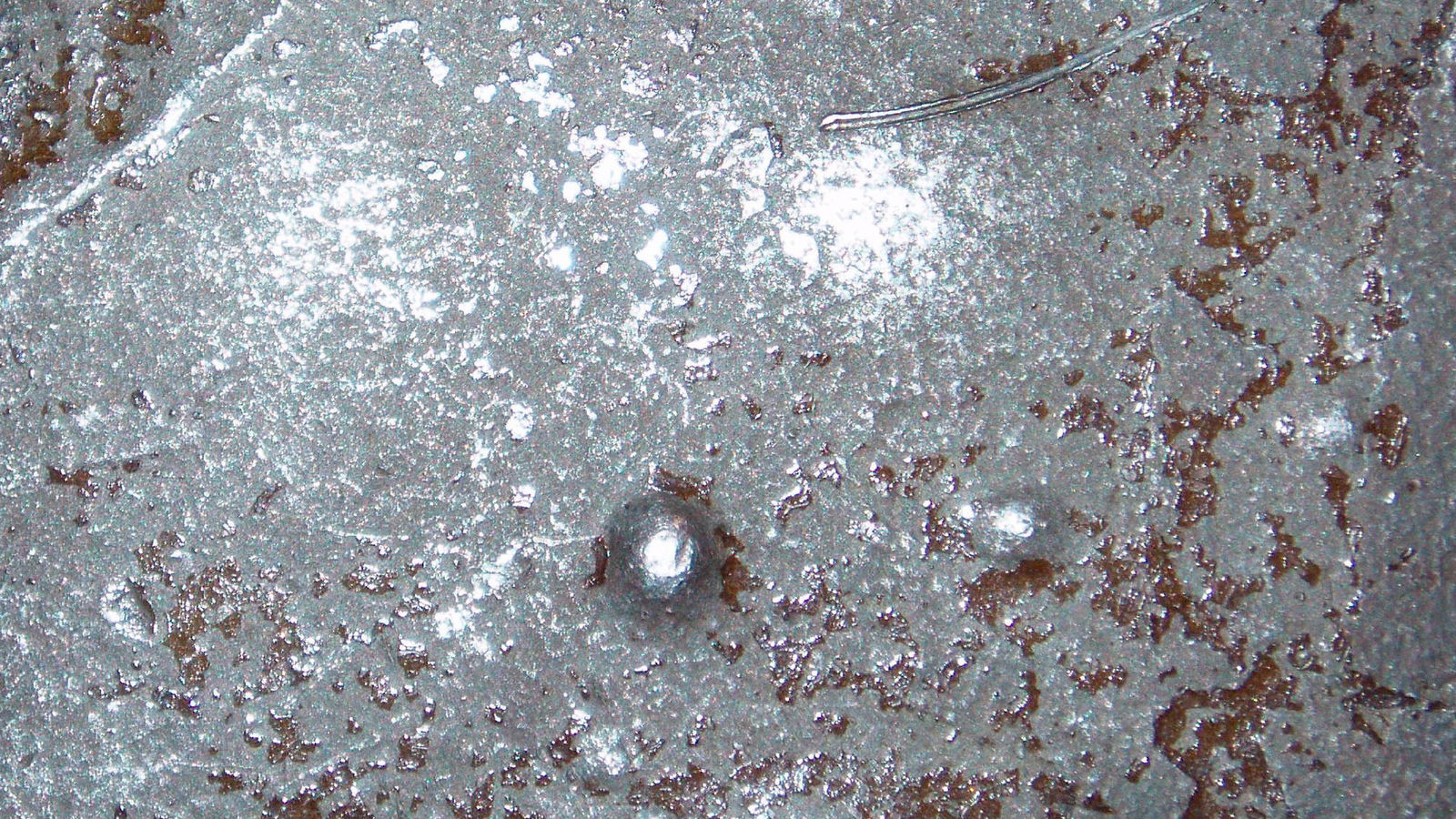

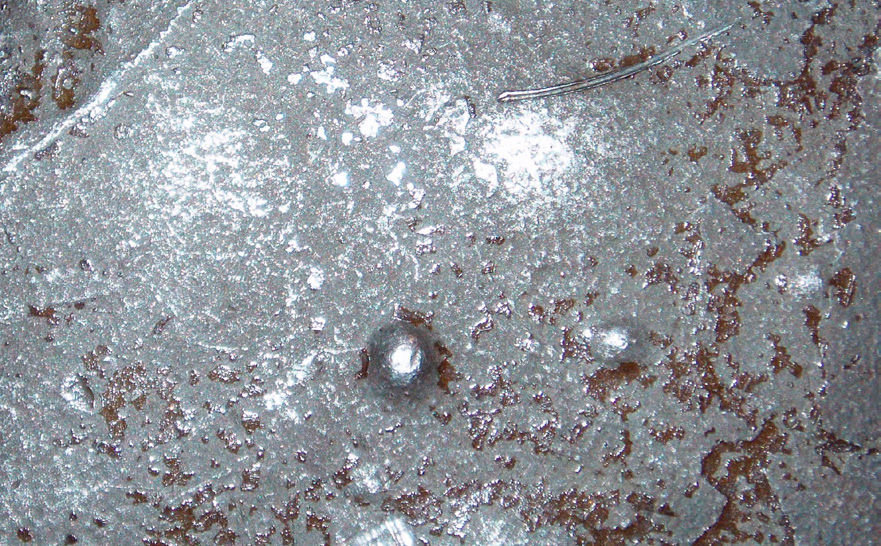

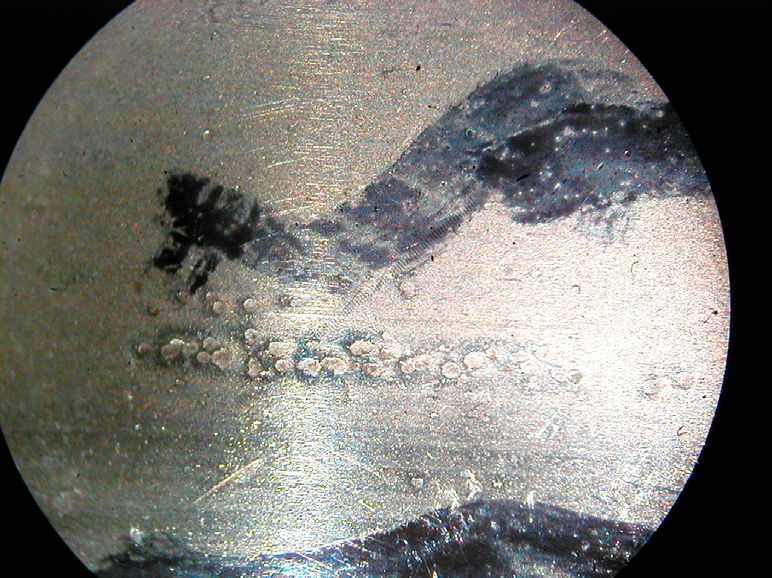

Typically, as engineers and technical people, we know that steel corrosion involves oxygen atoms uniting with the iron atoms in the steel. We realize this reaction slowly thins the base metal, and that the steel or iron part could eventually crumble into a pile of rust. But there are also times when the very serious dangers from corrosion are almost invisible to the human eye.

Two general classifications for corrosion are:

- Dry—at elevated temperatures.

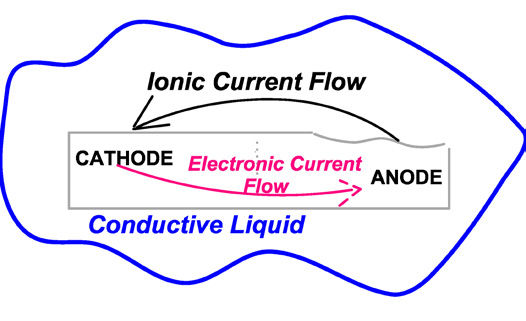

- Wet—where liquid is needed to conduct corrosion currents.

An example of dry corrosion is the scale that develops on grates of a barbecue grill. In those situations, the elevated temperatures supply the energy needed for the oxygen to unite with iron. Fortunately, dry corrosion is uncommon in the machinery world because the temperatures needed for it are in the range where specialty alloys and exotic lubricants are usually needed.

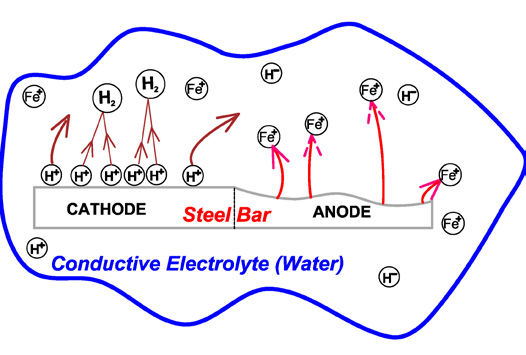

To understand wet corrosion and the problems it can create, Figure 1 shows a microscopic view of what happens in a typical corrosion cell. This shows the corrosion of a steel bar, and because of minute differences in the electrical potentials within the bar, the anode area is being attacked while the cathode area is protected. At the anode, Fe+ (iron) ions are released. (An ion is an atom with an electrical charge.) They are off in the liquid, usually water, and will eventually pair up with some oxygen ions to form the various forms of rust that we see all around us.