A Different Type of Wind Application for Aerospace Research

Two accumulator tubes of more than 80 meters in length run over an open space next to the building and pass through the solid outer wall to the inside: The enormous dimensions of the research facility become clear as soon as you enter the site around the Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology at the DLR in Göttingen. Inside, a giant vacuum vessel with a volume of 50 m³ is connected to the tubes. Detailed and fundamental studies are carried out there to investigate the fluid mechanics phenomena that are essential for adequately predicting the performance of supersonic aircraft. How can the aerospace vehicles of tomorrow become more environmentally friendly, safer and more efficient? And how can you use precise computer simulation of supersonic flight to evaluate new configurations while still in the design process? The scientists want to provide answers to these questions, and many others, with the tube wind tunnel. Vacuum technology from Busch is an indispensable part of these research projects.

The large-scale research facility was opened in the 1950s. Göttingen-based physicist and flow researcher Prof. Hubert Ludwieg developed a revolutionary drive system for intermittently operating high-speed wind tunnels, which enabled studies with supersonic and hypersonic flows to be carried out. He called this principle a tube wind tunnel – which to this day is also known around the world as a “Ludwieg tube.” In 1968, the Ludwieg Tube Wind Tunnel, Göttingen (RWG) was the first of these large-scale aerodynamic research plants in the world to be put into operation. It is still in use at the DLR to this day.

Experiments at supersonic speed

The operating principle of the tube wind tunnel uses the interaction of pressure and vacuum, where the accumulator tubes serve as pressure vessels in which the air is compressed. To prevent air condensation in the ultrasonic nozzle, which occurs due to the strong expansion and the associated cooling of the air, the accumulator tubes must be heated to simulate high supersonic velocities.

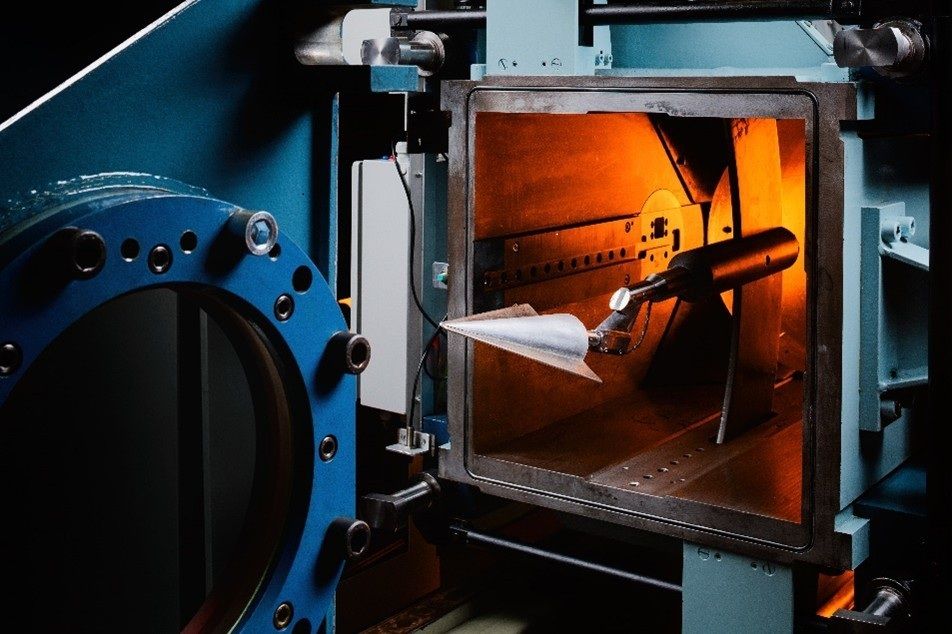

The accumulator tubes are connected to the ultrasonic nozzle via a quick-action slide valve. The measuring section is found at the end. This is where experiments are carried out. At the end of the measuring section is the vacuum vessel, which the vacuum pump is connected to. A vacuum slide valve between the measuring section and the vacuum vessel enables access to the measuring section as required. The vacuum vessel is evacuated using the vacuum pump. A COBRA NX screw vacuum pump from Busch Vacuum Solutions is used for this. It generates vacuum of approximately 10 to 40 mbar in the vacuum vessel. In the accumulator tubes, there is overpressure of approximately 2 to 40 bar.

To perform a test, the test model is placed in the measuring section using a movable model holder. Test models include aircraft models, sensors or material samples. Opening the quick-slide valve creates a running dilution wave that flows into the accumulator tube and accelerates the accumulator air towards the nozzle. Due to the differential pressure between the accumulator tube and the vacuum vessel, and thanks to the specially shaped ultrasonic nozzle, an ultrasonic flow is created in the RWG measuring section. Speeds of up to Mach 7 can be achieved – corresponding to seven times the speed of sound. Measurement times of up to 350–400 milliseconds are realized in the RWG. This is a peak value for wind tunnels of this type and gives researchers enough time to study the flow around the test models. During this time period, statistically relevant data or image sequences can be recorded to enable reliable data averaging and analysis.

More efficient testing thanks to vacuum

Vacuum technology is important not only for accelerating, but also for slowing down the high flow velocity. The air from the accumulator tube is collected in the vacuum vessel during the test and then discharged outside as normal ambient air. Dr. Erich Schülein, group leader and scientific supervisor of the RWG at the Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology, explains: “Thanks to vacuum technology, we can carry out the tests much more efficiently. Without it, we would not only have to significantly increase the boost pressure in the accumulator tube, but also the requirements for the stability of the entire system and the testing technology in order to achieve the required pressure ratio in the ultrasonic nozzle at all. The technical effort required for this would be enormous. The vacuum pump does this work for us. The combined application of pressure and vacuum accumulators makes it easy to change the pressure level and thus the Reynolds number of the flow.”